A model for Persuasive Communication

A model for Persuasive Communication ensuring Brand Effectivenss can be achieved more systematically and used to underpin “taste”.

Article Summary:

Persuasive communication works through meaning, not just attention. Attention is necessary but is really just the first step in bringing about a desired change in behaviour. What drives memory, motivation and behaviour is an encoded meaning within an image.

I propose a systematic model for analysing meaning in images. Drawing from anthropology, neuroscience and behavioural science, the model maps how ads activate psychological “triggers” that shape preference and agency.

This model is an empirically-proven set of 10 behavioural ‘forces’ organised into 3 clusters: meaning, desire and belief, which provide a structured language for diagnosing how creative influences behaviour.

Semiotic + Computer vision (AI) analysis shows different ads activate different forces. Case studies like Nike Dream Crazy, Fearless Girl, VW Lemon and Morgan illustrate how successful communications build preference via elevated symbolism, identity, status, or liberation, not rational claims.

The implication: brand effectiveness can be made more systematic. Pairing the 10 forces with audience insight, measurement and media planning offers a way to engineer repeatable persuasive creative that moves beyond “sea of sameness” and performance dopamine hits.

The Question

Have you ever asked yourself why you liked a certain image?

Or questioned after the fact, why something may have played a role in persuading you to do something, to get something…to buy something?

Most of us don’t consciously track how images shape our behaviour but psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology all show that they do.

Why and crucially how something is persuasive has been examined before. Particularly in advertising because let’s face it, if something isn’t persuasive - in some way - then really what is the point of it at all?

What we rarely have is a language for what kind of meaning advertising messages are activating.

“What we rarely have is a language for what kind of meaning advertising messages are activating.”

Origins & Hypothesis

With my formative years at Facebook (now Meta) and shorter stints at both Google and Pinterest I can accept that culturally, I have a bias ensuring as much of a go-to-market strategy can be systemised as is reasonable. This is ultimately how you can bring into effect things like the 70:20:10 principle and how you can build scalable repeatable patterns for success. As someone put it once when discussing performance marketing ‘we’re all trying to find the perfect recipe but the ingredients are always changing’. With the media levers that drive impact this is much more easily quantifiable. However, figuring out what’s in a “brand idea” that ultimately makes it successful is much harder. If strength of “brand” is another way of saying "preference" - how might that sense of preference be cultivated? And, is there even a way we might do this systematically?

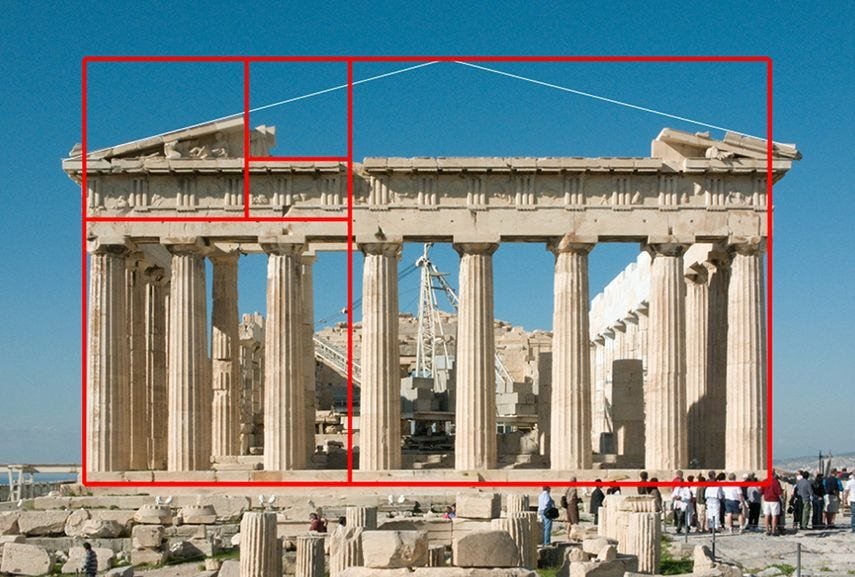

In 2019, while at Ad-Lib I wrote a product requirements document using Google’s Cloud Vision as the foundation for an insights tool which would use image recognition. This would be a brilliant “upper funnel weapon” for the company. The idea was to apply Fibonacci's understanding of what is desirable and symmetrical in nature as a hypothesis for understanding image composition. In theory we could join up what was structurally arresting within an image, pair it with performance data it was able to generate and prove or disprove image quality using this methodology.

Image recognition was young at the time and this idea morphed into what we codenamed the “Collybot” - leaning on the (legendary) Patrick Collister. We would use his smarts as a proprietary semiotic scoring system. Patrick wrote the “Acrington Stanley Ad” one of the most loved pieces of communication the UK has ever seen. He knows a thing or two about winning hearts and minds and, I’m proud to say sits on the Dark Horse Advisory Board.

Fast forward to today and image recognition is at a level where we can understand people, objects and pixel colours with a high degree of confidence. The point being that if image recognition can transcribe what’s in an image to a text-based description, then sharing this description with a behavioural model - with knowledge of what communication is persuasive, either directly or via some form of Natural Language Processing (NLP) interpreter - we are going to be able to understand the persuasive cues in a piece of communication which consists of a group of pixels. This concept becomes “super-charged” when we analyse a piece of communication made up of both an image and text, as the vast majority of advertisements of course are. In general, ads that pair images with text have superior recall: the image grabs attention and provides context, while the copy anchors the intended meaning.

This all leads to a final hypothesis: If branding works then it stands to reason that ‘meaning’ and behavior change are related. We can explore the strength in this relationship.

The Parthenon, Athens. The Golden Ratio in architecture is now visible in many bands logos like Apple (photo credit: Kimp)

“If branding works then it stands to reason that ‘meaning’ and behavior change are related.”

Challenge & Solution Statement

How should a model for behavioural change be constructed? There are a number of models out there on behavioural change: COM-B, the Fogg Behaviour Model, MINDSPACE, Robert Cialdini’s principles of influence, and EAST, as well as foundational decision frameworks like Signal Detection Theory. Furthermore, there are institutions with a rich back catalogue of research into the things that really make us change our minds and, as a result, our behaviour – the Behavioural Dynamics Institute in particular. These frameworks are widely used in policy, health and social marketing, but there is relatively little published work on their systematic application to mainstream brand advertising and creative diagnostics.

The current dialogue on persuasiveness focuses very largely on ‘attention’. I’m sure this is no co-incidence given the big players in the ad Industry are a) digital (so transient) and b) offer up little in terms of “real estate” for advertisers to work with. Newsfeed type placements would be a prime example or “fucking postage stamps” as I recall one client saying when I was at Facebook in 2015 - is really all that’s on offer to persuade someone of something.

Now, I acknowledge I’m not making much allowance for the role of things like frequency, repeatability or distinctive brand assets in ultimately having a role in shaping our behavior but my contention is more: is it any wonder that the research into effectiveness has become about how to win “attention” in these digital environments? Of course not. That is the most rational argument these services can make.

A secondary issue is that of the performance marketing ‘dopamine hit’ where these channels are particularly dominant. I’m referring to the semi-instant gratification of making decision ‘a’ and its resulting outcome ‘b’ with a short time delay - maybe something like 1-2 weeks. It produces a feel-good factor associated with short-term decisions which is more in-hoc with board reporting cycles than the steady upside achieved by producing something of meaning. Binet & Field’s analyses of the IPA Databank – and later work from the likes of System1 Group – famously showed that long-term brand building tends to outperform the pure performance ‘box of tricks’ over time, but most boards, in my experience, don’t have that kind of patience. Maybe that’s a result of more P.E. ownership for mid-market businesses? That’s a conversation for another time.

The key point is that grabbing attention sits at the intersection of neuroscience and psychology – and if you can “stop someone’s thumb” - good for you - but does that automatically mean that the ad made a real impression on you?

The emerging consensus is that attention is necessary but not sufficient: it’s a bottleneck for effectiveness, but the meaning encoded in the creative determines what actually gets stored in memory and motivation once you’ve earned those seconds of focus. There’s active research linking attention, memory and choice, but far less that explicitly models different patterns of meaning as the bridge between what people look at and what they go on to do.

One thing I think we all agree on is we’re in the midst of a “sea of sameness”, “AI Slop”, perhaps even on a path to “dead internet theory”. Whichever way you choose to dress it up, I think it’s pretty clear there is a need, perhaps now more than ever, to understand and get a grip on creative matters. By ‘getting a grip’ I mean a) understand what persuades people to change their behaviour and b) to think about how marketing communications can do more than ‘make someone aware’ of something. That’s half the job. Marketing communications must be meaningful to their audience to be impactful.

Understanding what’s meaningful is an anthropology problem. So by building on what we know through anthropology - i.e. what is really fundamental to a person’s world view as it relates to their lived experience; things like culture, desire, someone’s social group and even their deep inward belief system are things which are better explained through anthropology than just about anything else.

To uncover what sits beneath this idea, I have taken a 3 pronged approach:

Research only empirically proven foundations in anthropology

Respect the neuroscience and where possible complement the existing research

Synthesize with existing and proven behavioral frameworks

The research effort touched on the works of 17 authors who, between them, have tens of thousands of citations. Almost all of this work sits in fields outside day-to-day marketing and advertising. By contrast, much of the most-cited marketing science - including the Ehrenberg-Bass canon, perhaps the most respected body of marketing science in our industry - lives squarely within a marketing context.

The major provocation is that Ehrenberg-Bass Institute and other industry luminaries such as say, Binet & Field, offer empirical patterns of how brands behave: understanding how and why people respond with cultural, emotional and behavioural nuance which bridges product, audience and message is what forms the intellectual backbone of what has come to be the Dark Horse behavioural model, and although empirically-proven is, it strikes me, underused in the analysis of marketing communication.

In other words, while Ehrenberg-Bass and Binet & Field offer empirical patterns of how brands behave, there is room to build on this and address why people respond with cultural, emotional, and behavioural nuance that bridges product, audience, and message.

“While Ehrenberg-Bass and Binet & Field offer empirical patterns of how brands behave, there is room to build on this and address WHY people respond with cultural, emotional, and behavioural nuance that bridges product, audience, and message.”

These people might know you better than you know yourself…

Building The Dark Horse Behavioral Model for Persuasive Communication aka. “10 Forces”

The first thing the research reveals is a clustering behavioural “triggers” into 3 core buckets. As a casual observation, these statements struck me as being simple and so intuitive:

1) The Power of Meaning

People connect with stories that feel timeless, sacred, or rooted in tradition; it makes products feel more meaningful or elevated.

People make decisions by spotting differences, showing a sharp “before vs. after,” or “old vs. new” helps them choose.

When something breaks the expected pattern, it grabs attention, especially if it challenges norms or flips the script.

Simplicity and effortlessness are often communicated via contrast (old way vs. new way, hard vs. easy). It supports structure and salience.

“How humans use stories, symbols, rituals, and oppositions to make sense of the world and shape behaviour”

The Sistine Chapel exemplifies triggers of ‘contrast’ and ‘tradition’ in it’s repetoire for capturing our attention

2) The Politics of Desire

People are drawn to things that reflect who they want to be. Things like status, beauty, success, or belonging.

People want what other people seem to want - popularity, trends, and recommendations help them decide.

In cultures where norms feel imposed or overused, people respond to brands that break the mould or rebel.

Scarcity, time-limited access, or cultural urgency taps into status, reward, and even emotional arousal, which all desire-driven.

“Desire is shaped by cultural representation, global power dynamics, and who gets to define what’s aspirational.”

To prove the point: really impractical fashion choices seem perfect! Status as a mode of life. Image Credit: Nicolas Walraven van Haften (Dutch, 1663–1715). Portrait of a Family in an Interior, about 1700. Oil on canvas; (18 1/4 x 21 7/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1982.139. Charles H. Bayley Picture and Painting Fund. Source: MFA Boston

3) The Loop of Belief

People act when they feel confident they can. Showing how something works helps reduce hesitation.

People often take cues from others - reviews, bestsellers, and social trends help them feel safe or “in the know.

People like brands that show self-awareness or challenge tired ideas - especially when they feel seen or included in the joke.

“We form beliefs by referencing what we think others think, and how self-aware messaging influences trust and behaviour.”

The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. The “social proof” of doing something silly - and for a good cause. Photo Credit: USA Today

These (ahem) buckets of behaviour infer that within them there are 10 fundamental triggers which we can codify for semiotic analysis as well as being harnessed by a person or business wishing to convince their audience to do a “thing”. These are the 10 forces. 10 forces which, if applied in the right way at the right time to the right people should, empirically-speaking have a better chance of changing behaviour than not.

“10 forces which, if applied in the right way at the right time to the right people should, empirically-speaking have a better chance of changing behaviour than not.”

1) Assurance

Assurance speaks to the part of us that wants to feel safe and informed before committing. It builds confidence through proof: credentials, guarantees, certifications, awards, ratings, expert backing, warranties, or transparent comparisons. The tone is measured and professional, avoiding hype.

Brands use Assurance when buyers worry about making the wrong choice, when stakes feel high, or when expertise matters (finance, healthcare, B2B, automotive, premium appliances, schools, legal, travel, insurance). Rather than stimulate excitement, it reduces risk.

2) Care

Care works by making the audience feel understood, protected, and tended to. Rather than proving competence, it offers empathy. The trigger is emotional safety. It says “We see you, we care about your needs, and we will look after you.”

It shows up through warm language, family cues, wellness framing, testimonials about compassion or support, and visuals that soften the hard edges of decision-making. Care is crucial when the product touches home, children, health, comfort, or vulnerability. It lowers anxiety not by evidence but by nurture.

3) Control

Control channels mastery, precision, and the promise of predictable outcomes. This trigger appeals to people who want tools that work exactly as intended. As a mechanism for communication, it’s often fast, efficient, technical, and unambiguous.

The voice is confident and exacting, often backed by metrics, performance charts, tests, and “before/after” comparisons. Control is common in B2B, productivity, engineering, sports tech, vehicles, optimisation software, and anything where performance is quantifiable. It reassures, but unlike Assurance, it is not about safety it is about capability.

4) Desire

Desire invites the audience to imagine themselves transformed, elevated, or adorned. It trades in aspiration, sensuality, and identity. The feeling of wanting something beautiful, rare, or self-enhancing.

This trigger is abundant in beauty, luxury, fashion, travel, design, wellness, and personal expression. It often uses evocative visuals, slower pacing, and aesthetic seduction rather than proof or utility. It works by making the product feel like a pathway to a better version of oneself.

5) Discovery

Discovery is powered by curiosity. It gives people a reason to explore, try, or venture into something unfamiliar often through novelty, surprise, or hidden details.

The tone is playful, adventurous, and culturally plugged-in. Discovery thrives in categories where exploration is pleasurable (food, culture, gaming, interiors, travel, fashion edits, creator content, concept retail). It reframes consumption as learning, hunting, or uncovering something cool before others do.

6) Frictionless

Frictionless messaging removes cognitive and practical obstacles. It promises that the job will get done with minimal thought, effort, or time.

This trigger is dominant in e-commerce, delivery, mobile-first UX, fintech, utilities, and anything “mundane but necessary.” The tone is simple, ultra-clear, and free of fluff. Frictionless doesn’t try to seduce or surprise it simply makes the path to purchase effortless.

7) Liberation

Liberation is about breaking free from constraints social, institutional, historical, or psychological. It is energetic, optimistic, and often rebellious in flavour.

Brands use this trigger when they want to champion autonomy, ambition, or transformation. It works well in fitness, entrepreneurship, beauty, automotive, premium tech, creative tools, and self-expression categories. It casts the product as a source of empowerment, pushing the audience toward new possibilities.

8) Mythic

Mythic storytelling elevates a product or brand into the realm of symbolism, legacy, or cultural significance. It draws on archetypes (hero, creator, warrior, sage), origin stories, rituals, and narrative arcs.

The tone is timeless, serious, and dramatic, often invoking heritage or destiny. Mythic is common in luxury, sport, whisky, couture, automotive, national campaigns, and patriotic branding. It asks the consumer to join a larger story rather than just buy a thing.

9) Status

Status is about signalling prestige, success, and distinction. This trigger speaks to social comparison and recognition. It’s more than just being good, but being seen to be good.

Status thrives on cues like scarcity, endorsements, high craftsmanship, limited editions, discreet branding, or insider access. It is powerful in luxury, premium services, design-led brands, and professional categories where cultural capital matters. It doesn’t try to persuade emotionally, it confers hierarchy.

10) Tribal

Tribal is about ‘belonging’. It tells the audience: “These are your people, your culture, your signals, your values.”

It doesn’t rely on aspiration or exclusivity like Status, it relies on identity, community, and affiliation. The tone is inclusive, cultural, and often insider-coded. Tribal is evident in streetwear, fandom, subcultures, gaming, outdoor, lifestyle communities, and brands that rally like movements. The power here is safety, solidarity, and shared meaning.

Early Applications of the Model

To test the model I analysed images which have a) earned the plaudits industry-leading companies (I particularly like System 1), b) those which have won awards or c) brought about an undeniable change in behaviour. The idea being that these pieces of communication have been successful either in grabbing our attention or changing our behaviour which makes them good candidates for further study.

To be clear the 10 forces model would never say: “This image made you buy”

Instead it might say: “This image framed the choice as safe (or desirable, empowering, normal, prestigious - or some combination of all of these) and that framing altered the motivation or resistance of the people exposed to it.”

Think of it as a structured way of naming the meanings images activate and why those meanings predict what people remember, trust, or feel motivated to do.

Below are some sample readouts, which were generated by AI based on the an understanding of the manifest.json file which accompanies each analysed image. I have deliberately kept them this way because ‘Just Do It’ is treated as a core part of the meaning the communication wishes to impart but for someone who has spent years in the industry, it is a slogan I’ve seen so often, it has almost become “wallpaper”.

“Think of it as a structured way of naming the meanings images activate and why those meanings predict what people remember, trust, or feel motivated to do.”

Behavioural readouts:

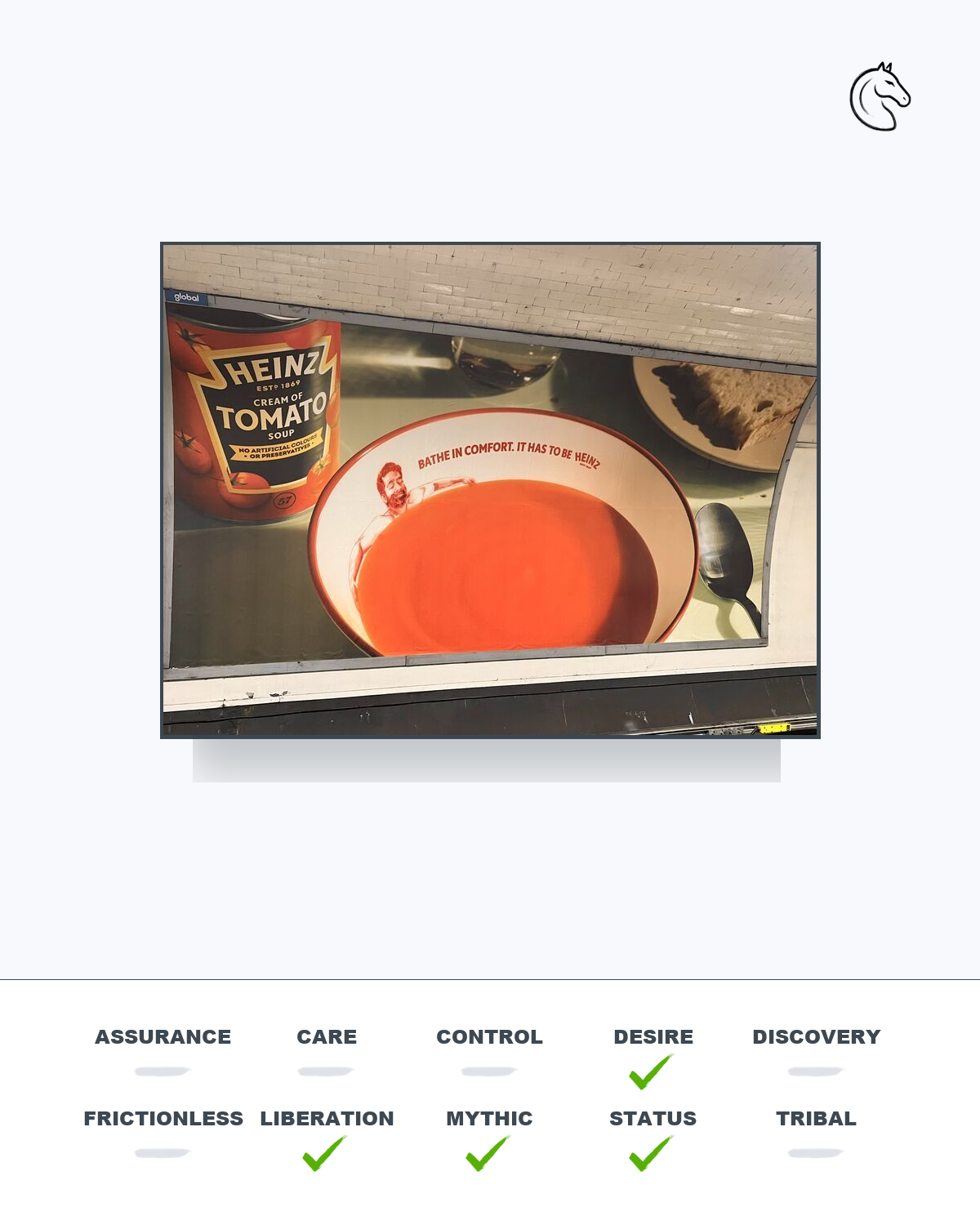

Heinz Baked Beans

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

This was rated as a top outdoor ad by System 1. Case-study reporting around the broader campaign links it to significant retail sales growth in some markets, along with award recognition, positive sentiment & engagement, and strong brand recognition testing.

Semiotic Analysis result:

Heinz soup bath is read as Desire + Mythic, with Status cues present but below the activation threshold. The velvet/marble surface codes bring in Desire, and the composition/figure treatment is flagged as Mythic Symbolism - it’s a surreal, almost ritualistic scene rather than a functional usage shot. However, the same premium cues that drive Status elsewhere don’t quite push the Status slider to PRESENT, which is a demonstration of the conservative nature of the mapping logic.

Behaviourally, it lands as a strange, elevated pleasure: familiar comfort food reimagined as a dream-sequence or icon, rather than as “everyday value” or “family care”. There is no Liberation, Control or Assurance-this isn’t about freedom, discipline or reliability; it’s about transforming the mundane into a weirdly exalted indulgence.

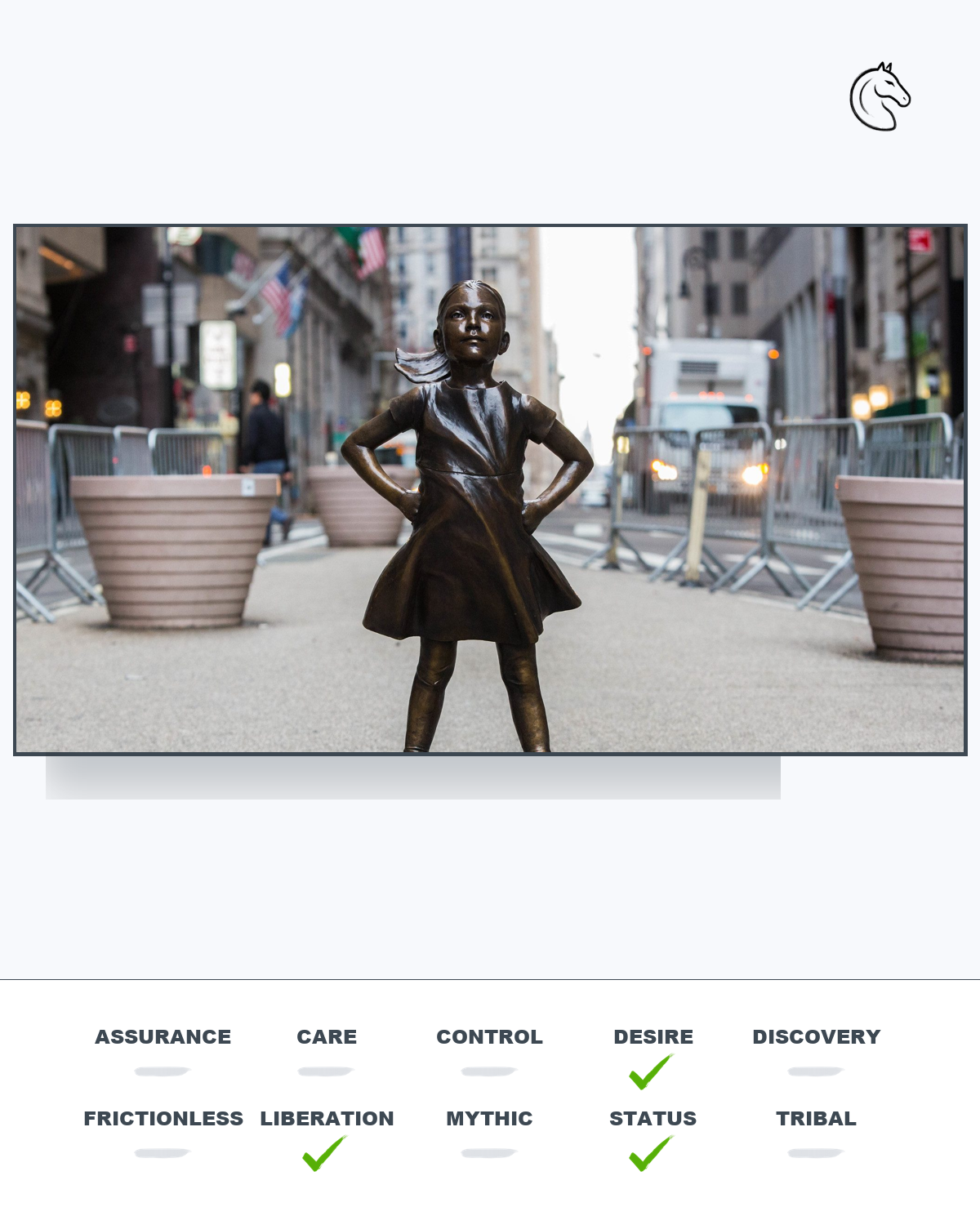

State Street: Fearless Girl, Wall Street

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

Massive visitation and social impressions are central to the case. SSGA+1

Semiotic Analysis result:

Fearless Girl in the system lands as a Desire + Liberation + Status construct. The material codes (marble/crystal) pull Desire and Status, positioning her as a premium, elevated object rather than a purely civic one. The high-contrast palette delivers Liberation, aligning with the act of standing firm in a previously male-dominated financial space.

Interestingly, Mythic does not fire here, so the model is reading her less as a timeless archetype and more as a polished, contemporary symbol of aspiration and defiance. Behaviourally, she becomes “aspirational courage in a premium wrapper”- a powerful stance, but one that leans more into upward mobility and elevated taste than into deep, old-myth heroism.

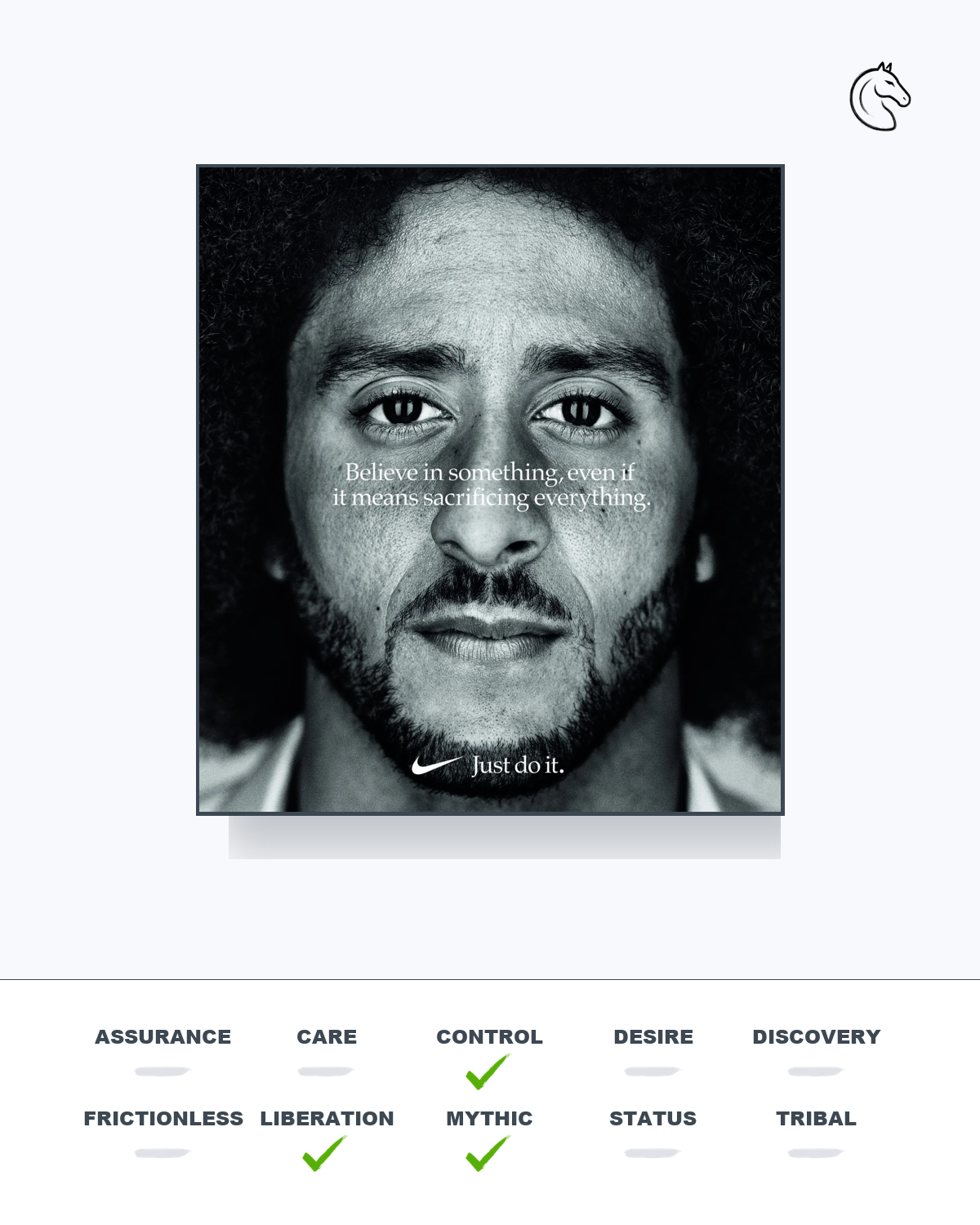

Nike Dream Crazy: (Kaepernick OOH / print)

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

Multiple outlets report ~31% online sales growth in the days after launch (based on third-party analysis), despite backlash. I would cite this ad as a major contributing factor to sports teams around the world (and across disciplines) ‘taking the knee’.

Semiotic Analysis result:

This execution codes strongly for Control, Liberation and Mythic. The high-contrast palette pushes Liberation- visually framing the work as a break from convention- while the “deadline footer” cue pulls in Control, adding urgency, discipline and consequence. Layered over that is a Mythic dimension: proportions and composition signal a larger-than-life narrative rather than a simple product shot.

Behaviourally, this reads as an act-of-will image: “step into something bigger than you, and do it now.” There is almost no luxury, status or frictionless coding here- it’s not about comfort or polish, but about resolve and transcendence. Commercially, it’s optimised for identity and mobilisation, not for reassurance or price justification.

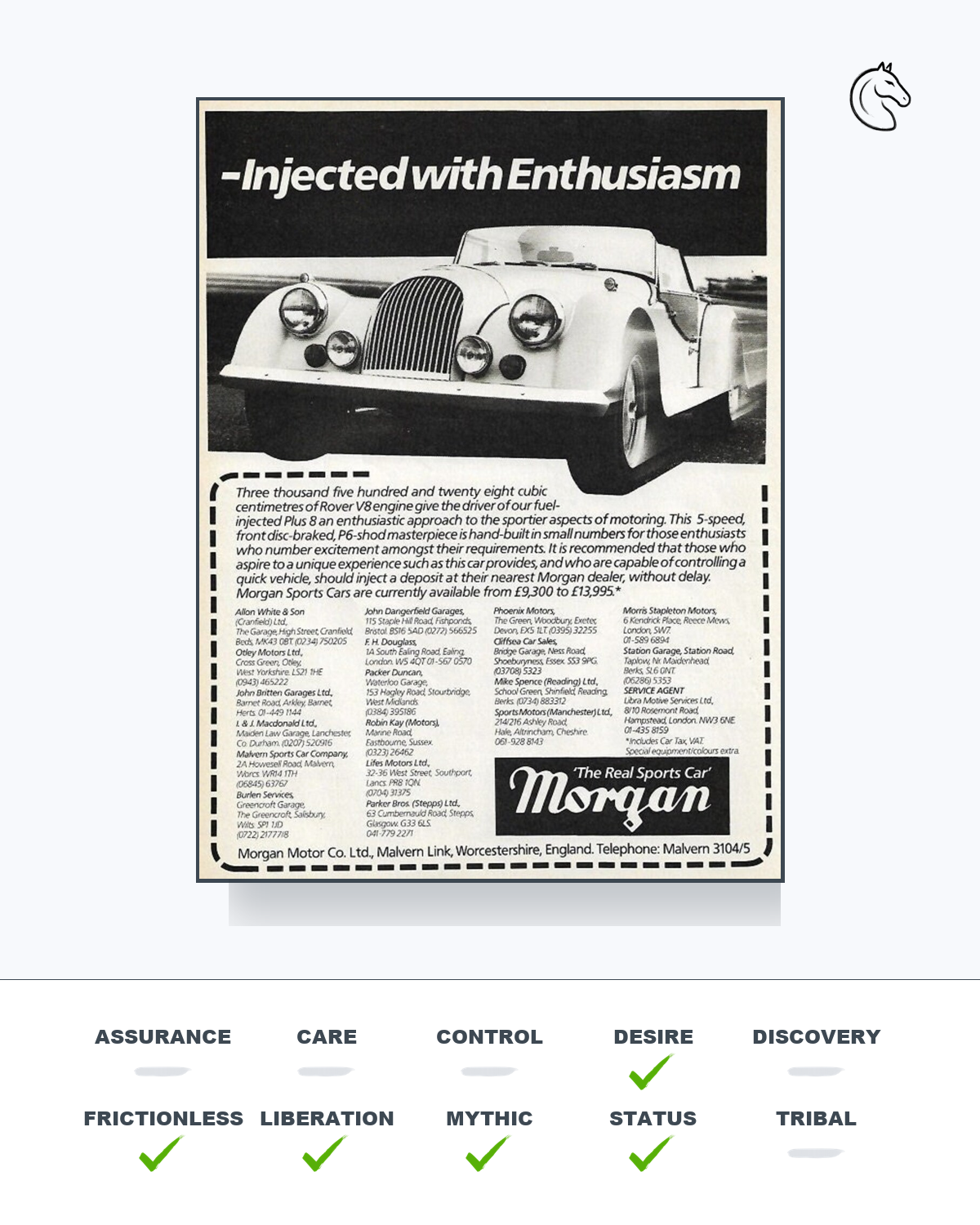

Morgan Motors

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

The fundamental design language of Morgan hasn’t changed in over a hundred years. The company has a distinctive brand asset which is the product and has been commercially successful through generations.

Semiotic Analysis result:

The Morgan creative hits the full luxury–mythic “stack”: Desire, Status, Liberation, Mythic and Frictionless all land. Premium material cues plus a luxury glow deliver Desire and Status; high contrast gives Liberation, while Mythic Symbolism suggests the car is more than a vehicle- an heirloom or legend. Minimal copy introduces Frictionless, making the scene feel effortless, unlaboured and confident.

The net effect is a quietly exalted object: a car framed less as transport and more as a totem of taste, freedom and lineage. There’s no Assurance or Care here-you’re not being persuaded on reliability or practicality. That’s behaviourally consistent with a luxury, discretionary purchase story: “If you know, you know; this is a world you step into, not a spec sheet you compare.”

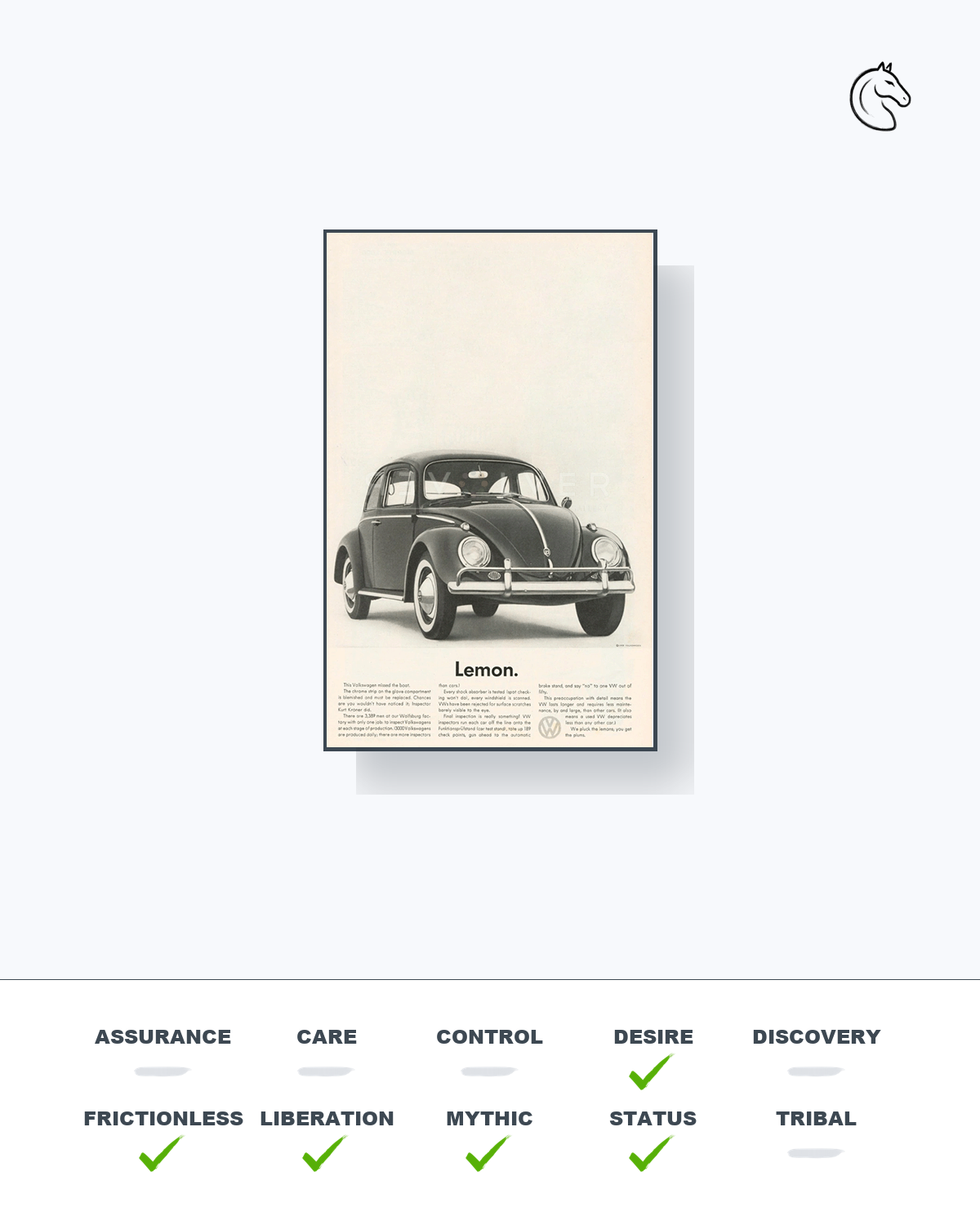

VW Lemon

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

Often credited with helping Volkswagen break into the U.S. market and shift consumer perceptions of the Beetle from an inferior foreign car to a trusted alternative to domestic brands.

Starch (an industry measurement agency) showed that these VW ads achieved higher recall and reader engagement than editorial content in magazines, which is a strong indicator of memorability and influence on attitudes (and a precursor to behaviour change).

Semiotic Analysis result:

The VW Warhol-style execution looks almost indistinguishable from Morgan in the model’s ontology: Desire, Status, Liberation, Mythic and Frictionless are all PRESENT again. The pop-art / minimal layout is read as Frictionless (minimal copy) and Mythic (symmetry, icon treatment), while the material / glow cues feed Desire + Status. High-contrast palette pushes Liberation.

Behaviourally, this reframes VW as an art object and cultural icon rather than a practical car, which is exactly what the Warhol pastiche is trying to do: move the Beetle out of “transport” and into “pop-cultural myth”. It’s less about reassurance and more about canonisation-the ad behaves like a gallery print, not a dealer brochure.

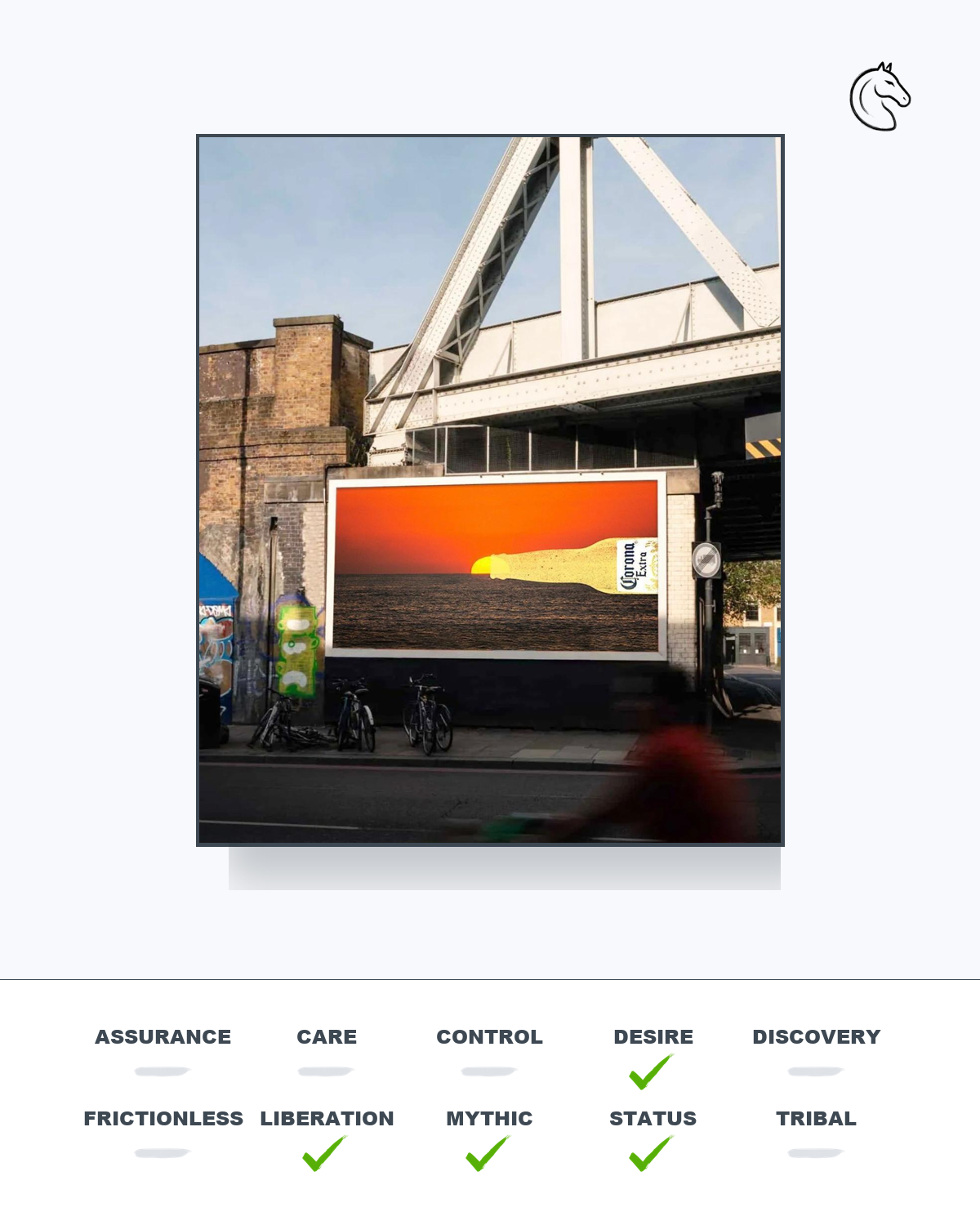

Corona

Why was it a good candidate for analysis?

Highlighted by System 1 as a particularly strong recent ad based on their taste (and mine I would add). The billboard demonstrated brand reinforcement and preference behaviours (dining choice, positive sentiment, increased distribution).

Semiotic Analysis result:

Corona’s sunset world combines Desire, Status, Liberation and Mythic. The material / surface codes (materiality codes in the model’s logic) push Desire + Status, the high-contrast sunset scene gives Liberation, and the combination of an iconic brand asset with mythic symmetry fires Mythic.

This is a classic brand-world halo image. It’s saying ‘you’re not just buying a drink; you’re buying access to a mythic, elevated moment of escape’. There’s no Frictionless or Assurance: nothing is making the choice easier or safer; instead, it leans entirely on symbolic upgrade and emotional transport - perfect for long-term equity, weaker for short-term rational conversion.

Next Steps

1) Paring with Audience understanding:

In order for the model to be useful in a campaign or asset/copy creation context , it needs to work in tandem with audience understanding. If we can reconcile what a person needs or typically responds well to from a communications point of view, then we can reconcile this with the 10 forces that typically bring about a behaviour change to have a better chance than not eliciting the outcome desired by communicating with them in the first palace.

2) Apply weights of each force:

The model could be more sophisticated in identifying the relative presence of each force, rather than simply identifying that they are present.

3) Cross-reference forces with performance data

While a campaign is in flight we could cross-reference performance data with the model to establish a robust data base split by industry vertical of the types of communication which are typically more salient in certain situations when trying to bring about a change in behaviour

Internally already, the forces interact with the media planning portion of the Dark Horse offering via an explicit contract which ensures that no amount of behavioral “shading” will eclipse the economic realities of unit economics and a profit target.

For now, I’m satisfied that we have proof of concept and have turned an idea into a pragmatic solution and system for understanding the meaning which a piece of communication imparts.